Personality

Structure of Personality

There are several theoretical approaches to describing the structure of personality. In the present work, the most widely accepted and empirically supported personality framework is applied.

The Big Five Theory

The Big Five conceptualizes personality as a hierarchical structure, with five broad higher-order traits at the top level. Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (OCEAN). Each of these traits is further differentiated into three lower-order facets, which capture more specific and nuanced aspects of individual personality differences.

O) Openness

I) Intellectual Curiosity

Interest in learning and thinking deeply.

A) Aesthetic Sensitivity

Appreciation for art and beauty.

C) Creative Imagination

Tendency to be original and inventive.

C) Conscientiousness

O) Organization

Preference for order, cleanliness, and planning.

P) Productiveness

Efficiency and persistence in completing tasks.

R) Responsibility

Reliability and sense of duty.

E) Extraversion

S) Sociability

Tendency to be outgoing, social, and talkative.

A) Assertiveness

Tendency to take charge and lead others.

E) Energy Level

Level of enthusiasm and spirit.

A) Agreeableness

C) Compassion

Caring, warmth, and concern for others.

P) Politeness

Tendency to be respectful and cooperative.

T) Trust

Tendency to assume the best in people.

N) Neuroticism

A) Anxiety

Tendency to feel worried and nervous.

D) Depression

Frequency of feeling sad or blue.

E) Emotional Volatility

Tendency to be moody and irritable.

Features as additional third Level

For the purposes of simulation and formalisation, an additional lower level is introduced. In the simulation proposed by R. Tobias, this level is referred to as features. Features represent specific self-attributed abilities of a person. These features are defined at a level of specificity that allows them to be readily interpreted and, at least in principle, objectively measured. Consequently, they can also be understood as properties of situations. For example, the degree to which an individual is exposed to criticism can be measured as a situational property, whereas the ability to cope with criticism can be conceptualised as an ability of the person.

When combined with a distributional representation, features can be used to describe individual preferences or tendencies, reflecting aspects of the self-concept. In this sense, a feature can be understood as a component of an individual’s self-concept.

Self-Concept

Describing Features as Distributions

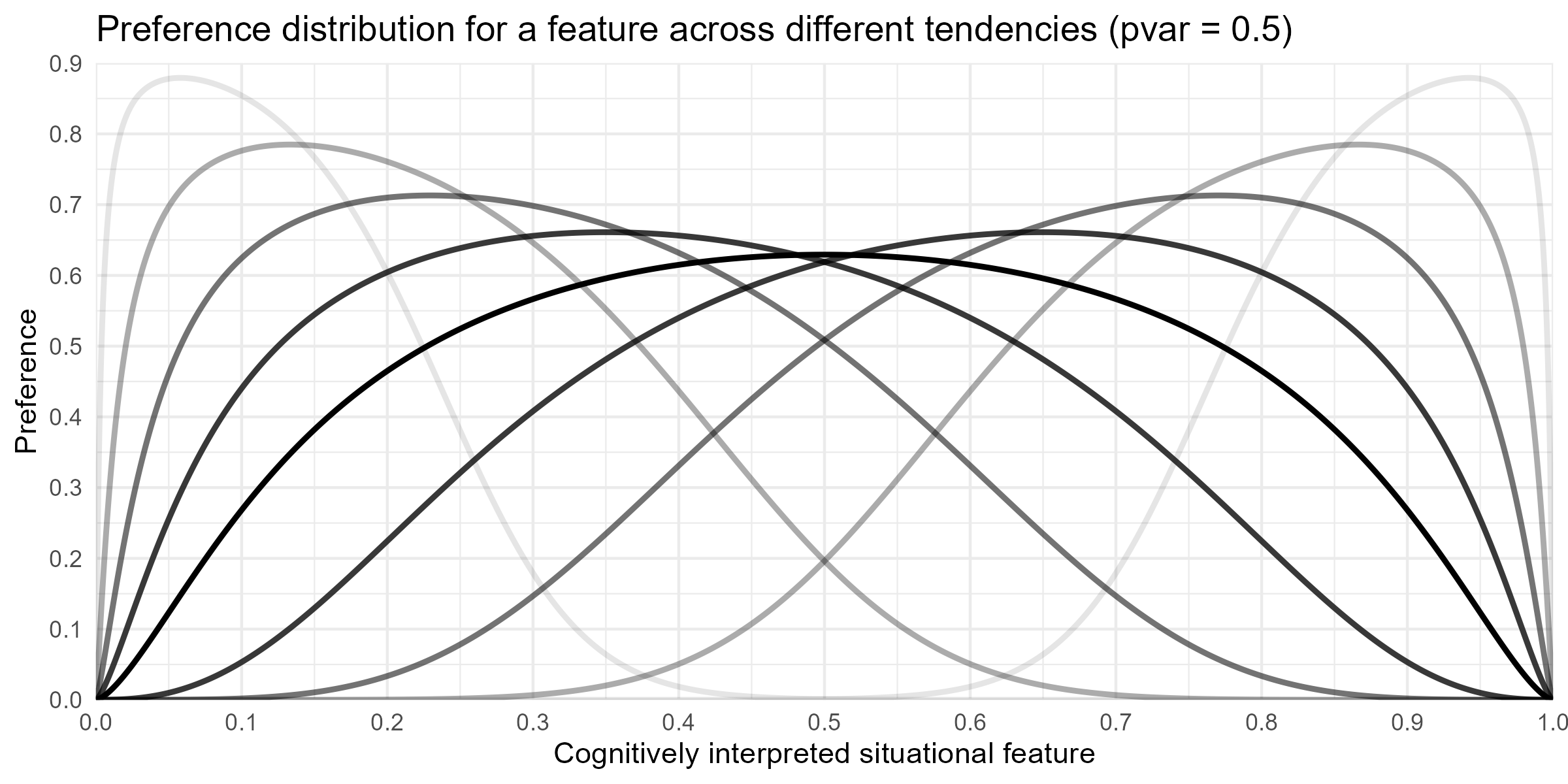

We assume that features can be mathematically represented by a beta distribution, characterized by a mean value reflecting the central tendency of the feature preference and a parameter pvar that describes its variability. > read more

The following plot illustrates the preference distribution for a specific feature. The x-axis represents the cognitively interpreted expression of the feature, while the y-axis depicts the corresponding preference. Accordingly, the curve reaches its maximum at the point where the individual feels most comfortable.

The curves presented above can therefore be described in tabular form as follows.

| Feature | mean | pvar |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| ⋮ | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| n | 0.9 | 0.5 |

Personality as Distributions

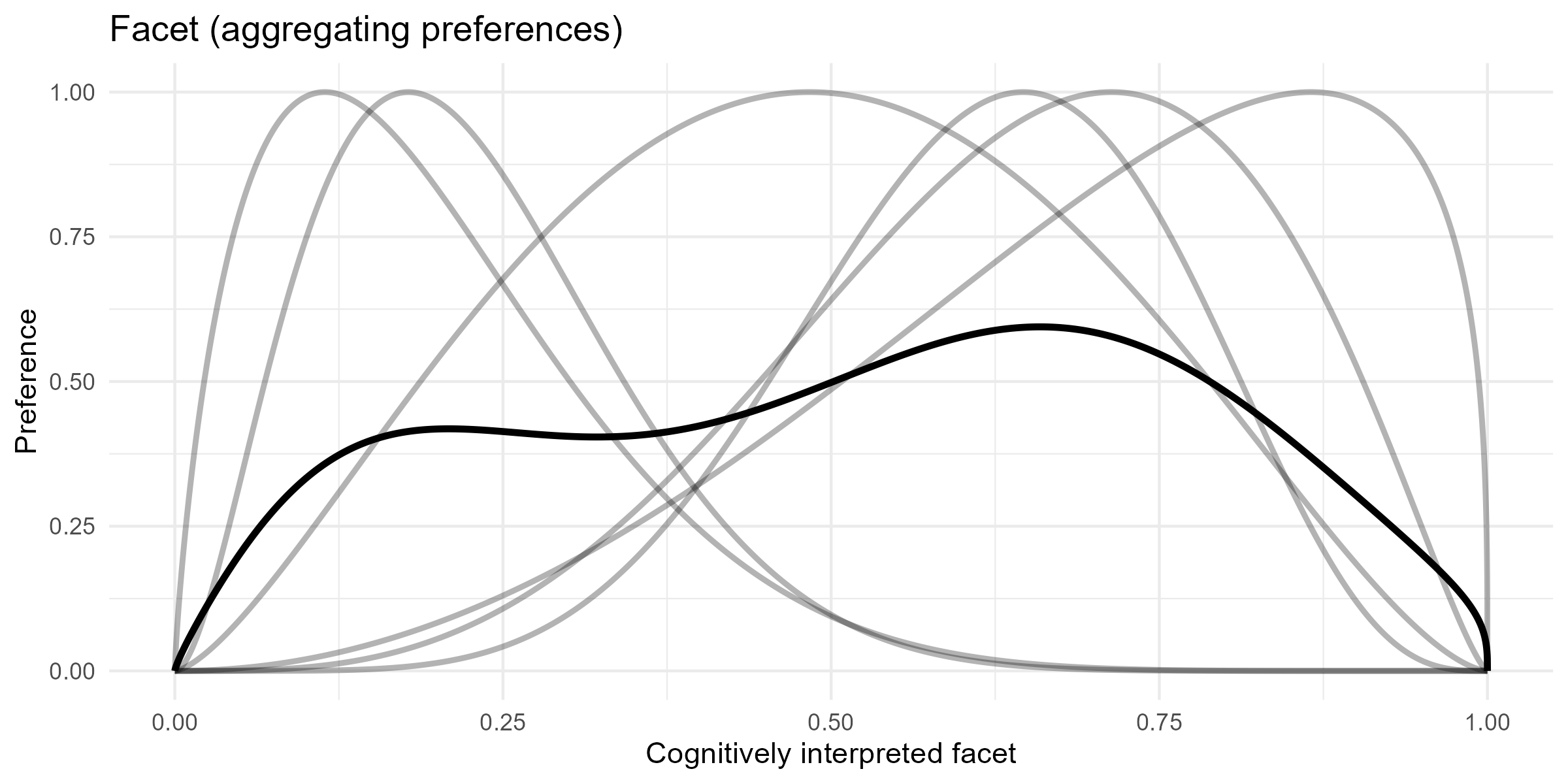

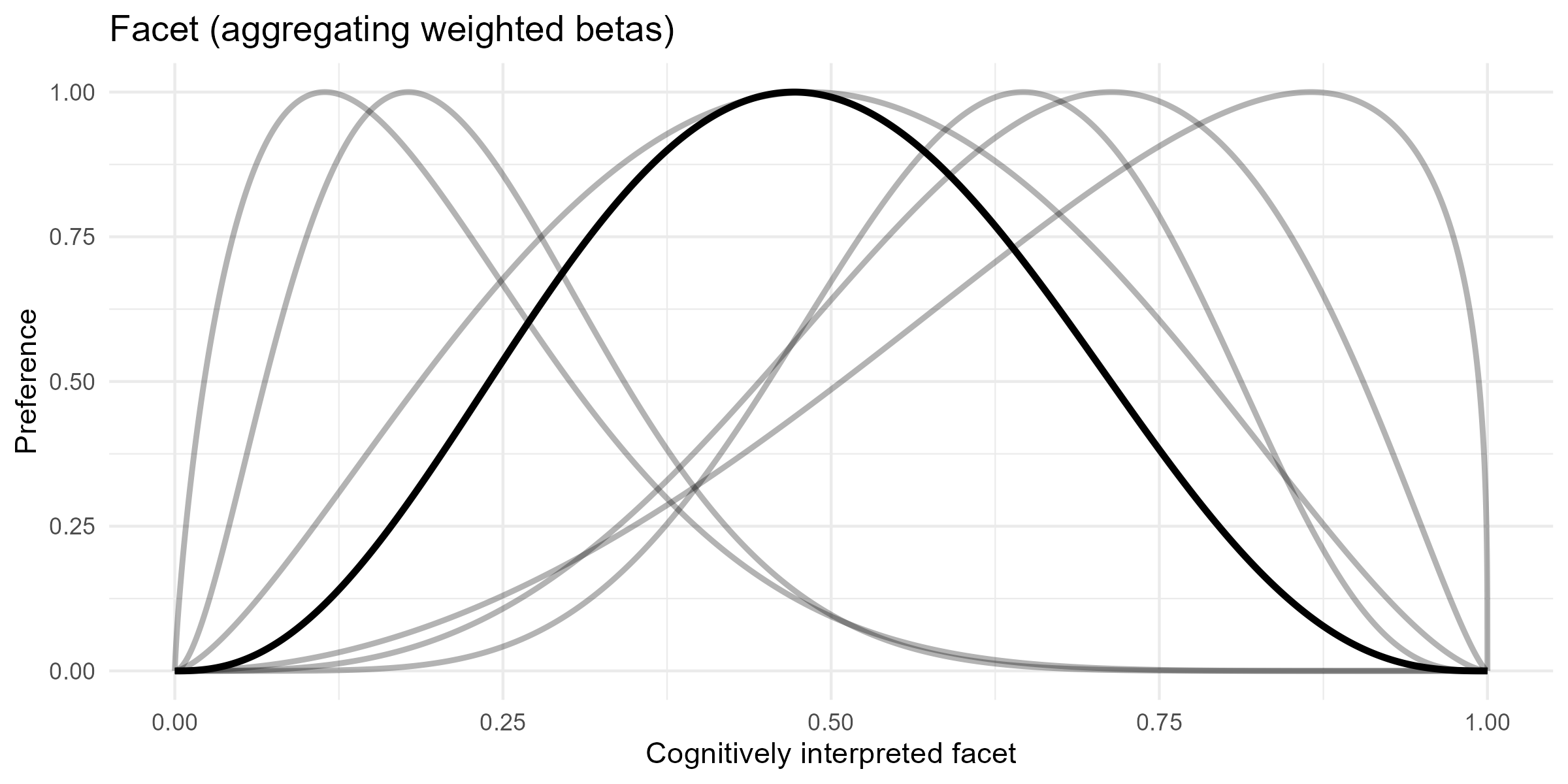

Based on the assumed hierarchical structure of personality, facets can likewise be represented as distributions. A facet distribution reflects the averaged preference distributions of all features associated with that facet. In the same manner, traits can be represented as aggregated distributions of their corresponding facets.

Therefore personality can be described in tabular form as follows.

| Trait | Facet | Feature | weight | mean | pvar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | I | 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| ⋮ | I | n | 1 - sum(1,n-1) | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| ⋮ | A | 1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| O | C | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| C | O | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

This raises the question of whether facets and traits should likewise be represented by beta distributions, or whether they should be modeled independently of any specific distributional form. Both approaches are mathematically feasible and therefore need to be evaluated on the basis of conceptual plausibility rather than technical constraints. > read more

Aggregating preferences

To aggregate preferences, the individual preference curves are summed directly and then divided by the number of features. An illustrative example of this procedure is shown below.

This approach may be problematic when features differ strongly, as it can result in a multimodal distribution without a clear tendency.

Aggregating beta parameters

A second approach is to average the beta distribution parameters. From these averaged parameters, a corresponding tendency and pvar can be derived.

Also this approach may be problematic when features differ strongly, as it can result in a facet-level tendency at which none of the underlying features exhibits a maximum. On the other hand, this raises the question of to what extent the features belonging to a given facet can realistically diverge in real-world situations.

Aggregating weighted beta parameters

A third approach would be to compute a weighted average of the beta parameters, using the inverse of the maximum as the weighting factor. This would reduce the influence of individual extreme features. However, this does not eliminate the problem discussed above. Instead, it results in a broader distribution, which may be considered more plausible.

Experiences

Regardless of the manner in which traits and facets are aggregated, the simulation operates at the level of features. Consequently, a form of memory must be defined at the feature level that allows distributions to be derived from accumulated experiences. To achieve this, the following components must be integrated.

First, an identifier is stored for each experienced situation, along with the time at which it occurred. As the main simulation operates in discrete steps, the step number is recorded as a running index of experiences. This will later allow individual situations to be located and manipulated retrospectively, for example in the context of interventions.

Each situation is associated with an open set of features. For simplicity, the corresponding facet and trait are stored for each feature. As it is currently unclear how many features define a facet and which specific features should be included, an additional weight is stored to specify the contribution of each feature to its associated facet. This facilitates grouping experiences by their features and enables the calculation of preference distributions.

For each feature, both an objective evaluation of its expression and a cognitively interpreted evaluation are recorded. This distinction will later be used to model cognitive bias.

In addition, an affective evaluation is stored for each feature, as well as an aggregated affective value for the entire situation. The stored value reflects the positive affect, which is derived from the corresponding preference distribution, negative affect is implicitly represented as its complement (1 − positive affect).

Furthermore, a behavioural factor is introduced to indicate whether the behaviour in the situation actually occurred. This factor is currently defined as a Boolean variable, where 1 indicates that the experience was directly enacted and 0 indicates that the situation was only imagined. Conceptually, experiences marked with 1 are intended to contribute to the computation of the self-concept, whereas experiences marked with 0 are used to define an idealised, desired self-concept.

Finally, because human memory is not perfect, an accessibility factor is defined for each experience. In line with the approach proposed by R. Tobias, accessibility is derived from situational affect. This makes it possible for experiences to gradually lose accessibility over time, in other words, to be forgotten. Consistent with assumptions in the main programme, positive and negative affect may decay at different rates.

For a simple example with four features, which load onto two facets that both belong to a single trait, the experience would be represented as follows.

| Sit. ID | Step | Trait | Facet | Feature | weight | Objective | Cognitive | Affective | Sit. Affect | Sit. Behaviour | Acc. Positiv | Acc. Negativ | Access- ablitiy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | n | O | I | 1 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | I | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | A | 1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| 1 | n | O | A | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1 | 06 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| 2 | n+1 | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

A test using several extreme and typical preference distributions shows that, by applying probability weighting to a randomly generated list of experiences, it is possible to recover the underlying preference distributions that were originally used. > read more

Link Functions

Ultimately, the simulation is intended to operate with only two inputs. The first is a characterisation of the agent, such as the self-concept described above. The second is a sequence of situations, each defined by objective feature expressions. To enable this, link functions are required that transform the given parameters into the quantities needed for the simulation. These link functions are outlined in the following section.

Cognitive Evaluation

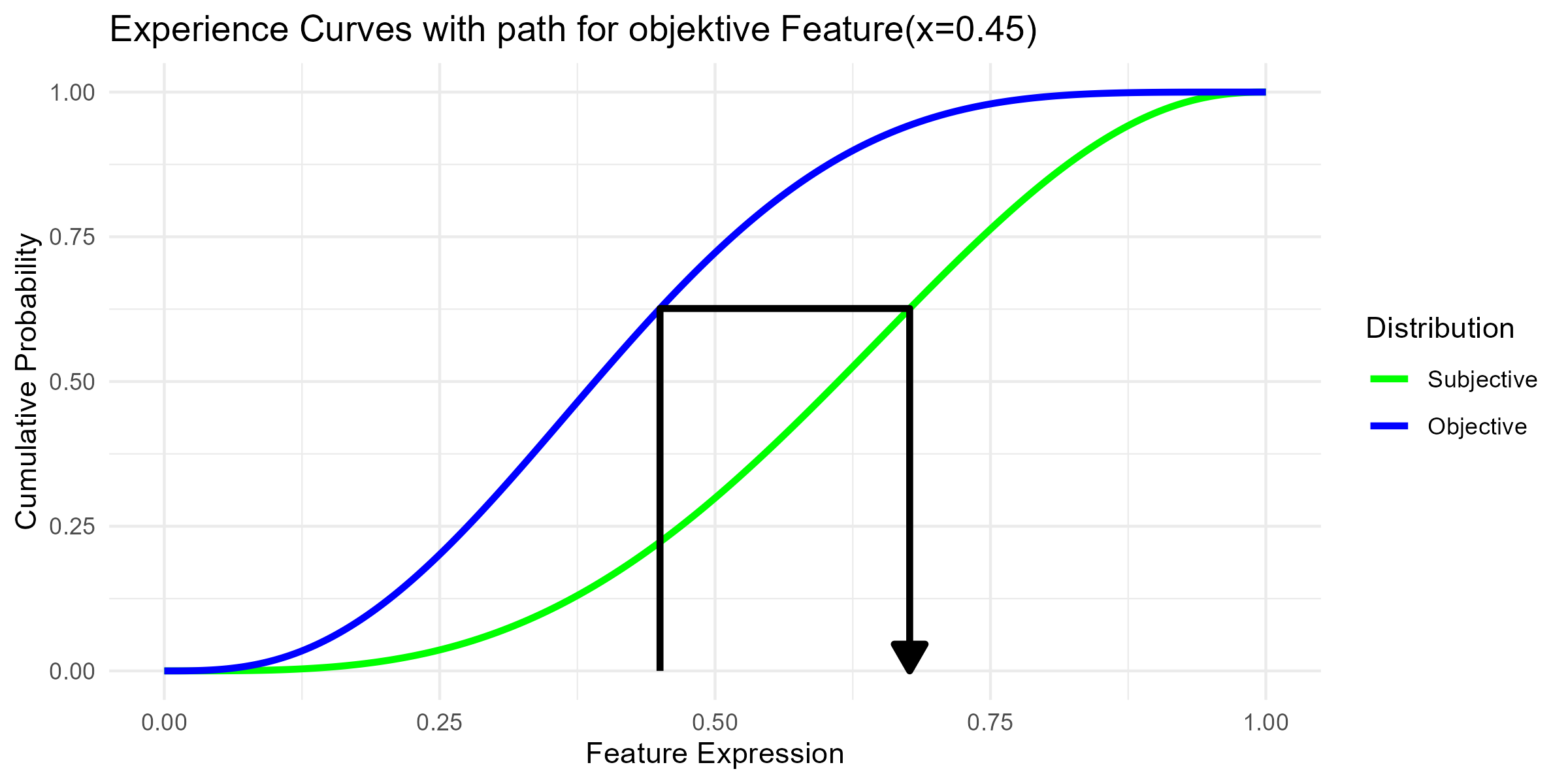

First, a function is required that transforms an objectively experienced feature expression into a cognitively interpreted feature expression. This transformation is based on the agent’s characterisation, specifically the cognitive bias. To achieve this, the cumulative probability is used. That is, the cumulative probability is computed on the curve of objectively experienced feature expressions. The cognitively interpreted expression is then chosen such that it yields the same cumulative probability on the curve of subjectively experienced feature expressions. In this way, the cognitive bias can be defined as the difference between the curve parameters, expressed as a shift in the mean and a scaling factor for pvar. > read more

Within the simulation, additional possibilities will be available to manipulate the computed cognitive interpretations. These manipulations will be described in more detail later in the section on interventions. Owing to the update function, such interventions are expected to lead to long-term adjustments in cognitive interpretation.

Affektive Evaluation

This mechanism represents the core of the simulation. As mentioned earlier, affect is determined by the self-concept, or more precisely, the probability of experiencing positive affect. The model assumes that there are two types of self-concept.

The first, referred to as the real self-concept, is derived from actual experiences that were truly enacted. At the technical level, only experiences with a behavioural value of 1 are included in its computation.

The second, termed the ideal self-concept, is based on experiences that were only imagined or reflect desired outcomes. Technically, this is computed from experiences with a behavioural value of 0.

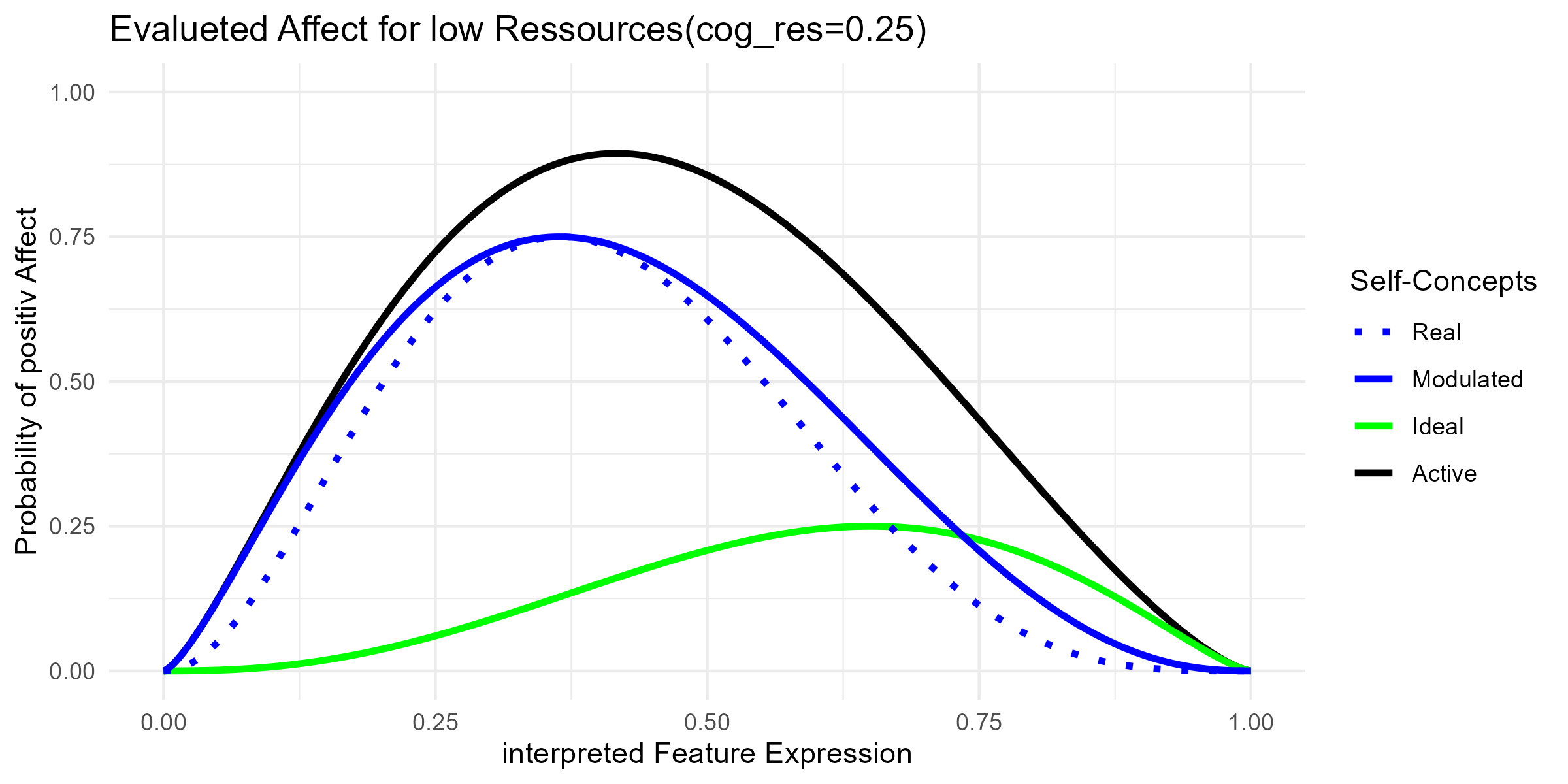

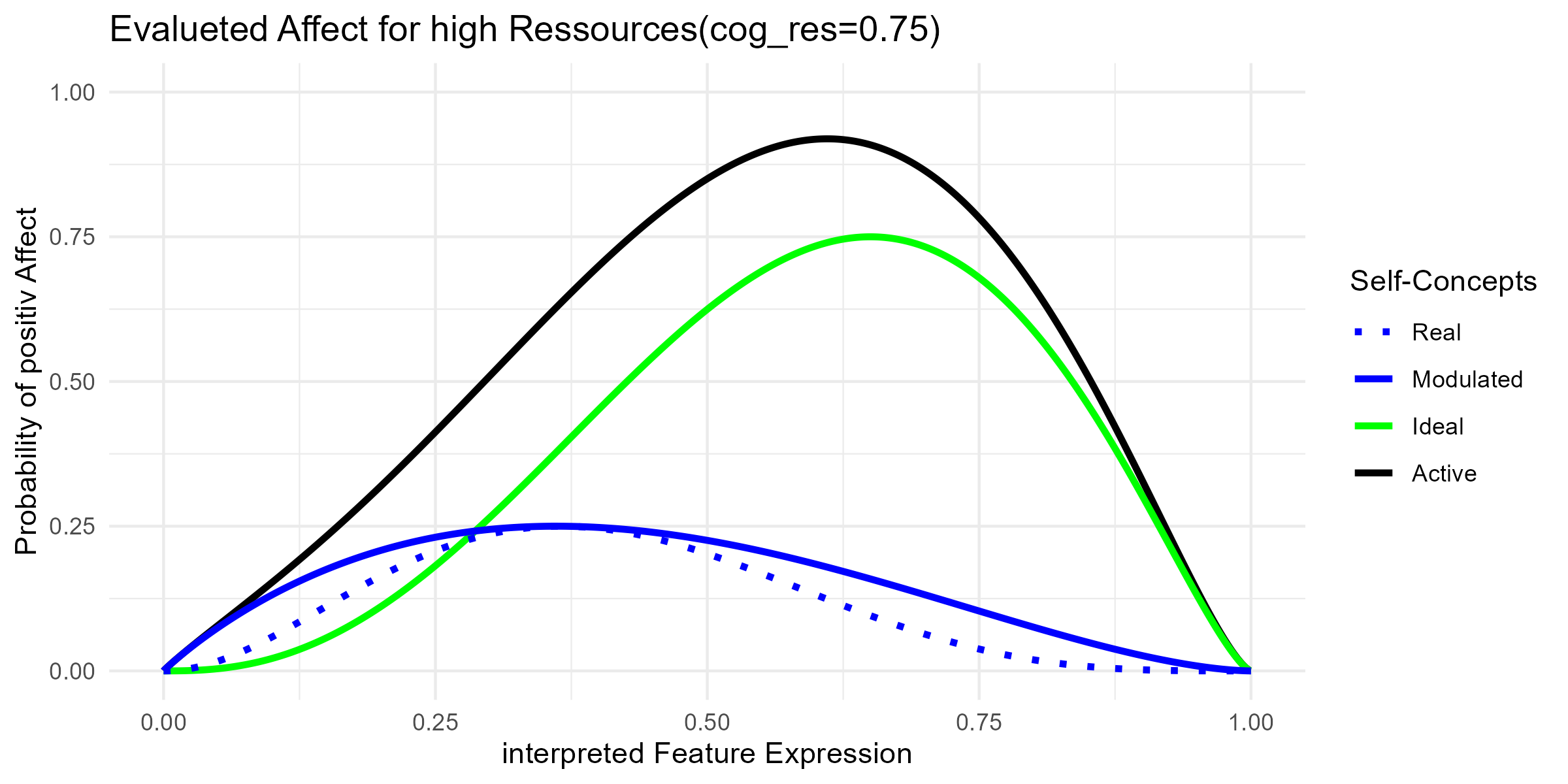

A weighting parameter determines the influence of these two distributions. In PersChange, this corresponds most closely to the factor of cognitive resources. When the weighting is 0, affect is determined entirely by the real self-concept, when the weighting is 1, affect is determined entirely by the ideal self-concept. This weighting can be interpreted such that, in situations requiring rapid decisions, behaviour will align more strongly with the real self-concept, whereas in situations with sufficient cognitive resources, individuals may prefer behaviour consistent with their ideal self-concept.

A further modulation concerns affective coping abilities. These operate on the variance of the real self-concept distribution, effectively broadening it and thereby increasing the probability of positive affect when a situation deviates from the central tendency. Thus, affect computed from the real self-concept can be understood as a purely reactive affective response, whereas the affect computed from the coping-modulated real self-concept reflects the regulated affective response, after affect regulation processes have been applied. > read more

Accordingly, in situations in which cognitive resources are limited, affect is evaluated primarily on the basis of the real self-concept.

In contrast, in situations with higher cognitive resources, affect depends more strongly on the ideal self-concept.

Habituation

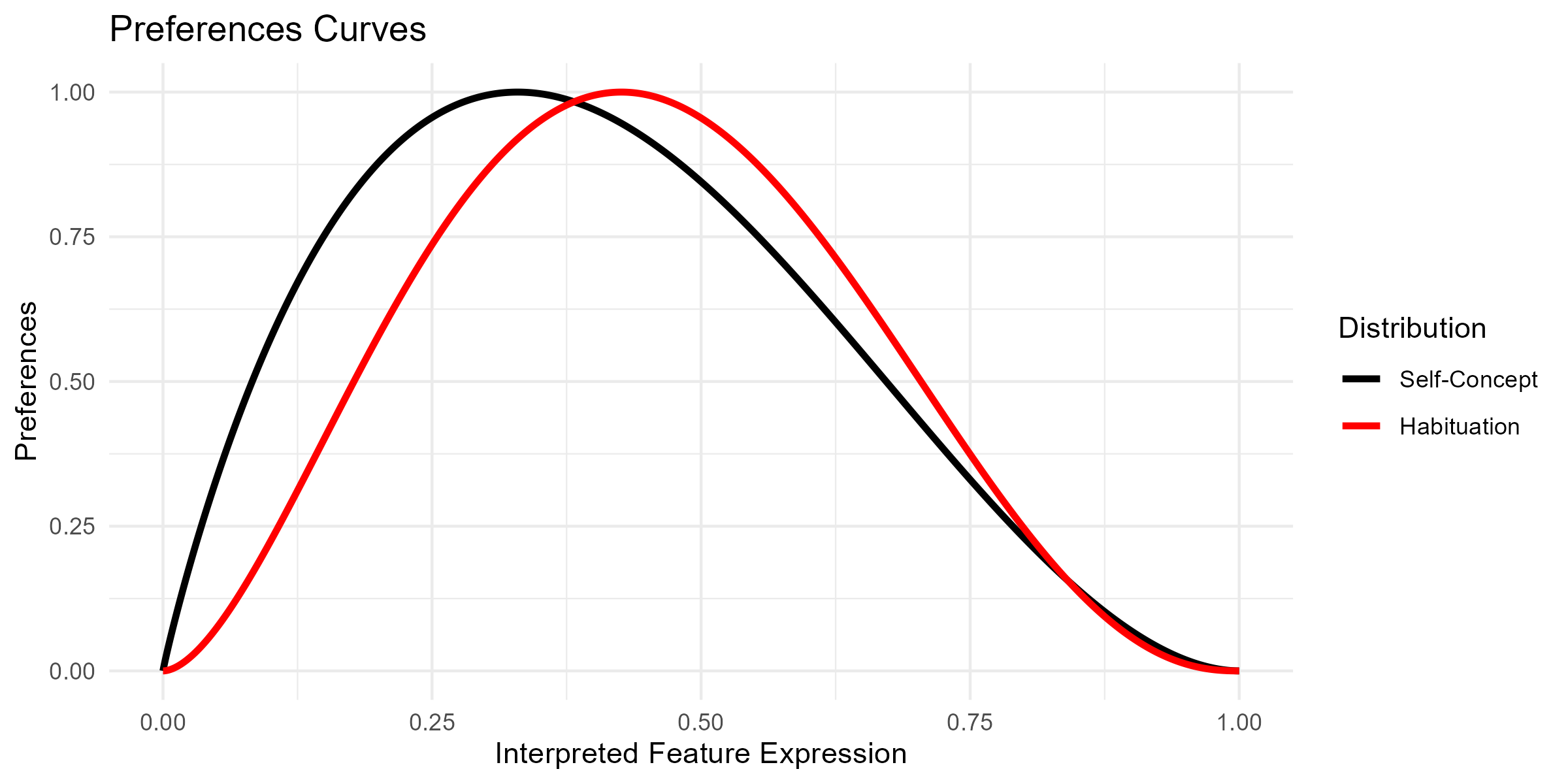

Conceptually, habituation is similar to the real self-concept. However, affective evaluations are not considered in this case. Instead, only the frequency of experiences is taken into account. Under normal circumstances, the mean values of the real self-concept and the habituation curve are therefore expected to be largely similar. However, they may also diverge. This divergence is referred to here as behavioural bias. In such cases, individuals may develop habits that do not maximise their satisfaction. This may occur either because individuals repeatedly engage in certain behaviours despite the availability of more satisfying alternatives, or because such alternatives are not available in the environment. > read more

Situation Preference Evaluation

At present, this aspect remains insufficiently specified and requires further exploration. It appears reasonable to assume that decisions for a given situation are based on the two concepts introduced above, namely the active self-concept and habituation. However, the manner in which these two components should be weighted remains unclear. As an initial approach, the two distributions are weighted according to their variance, such that distributions with lower variance receive greater weight.

It is nevertheless relatively easy to anticipate that a simulation using this preference setting will converge in the long term towards the dominant distribution, that is, the one with lower variance. This is because habituation and the real self-concept are expected to gradually align with one another over time. Consequently, both distributions may become increasingly narrow, as new experiences are predominantly added in regions that already correspond to existing preferences. This effect could pose challenges for the simulations. At the same time, it is conceivable that this represents a natural developmental process in which individuals increasingly engage only in activities aligned with their preferences. Such a mechanism may offer a potential explanation for the tendency towards greater centrality of personality traits in later adulthood, when external constraints decrease and individuals gain greater freedom in their choices.

In the PersChange simulation, a commitment parameter describes the degree to which an agent is committed to a given situation. This parameter allows behavioural enactment or situation selection to be influenced by situational demands rather than individual preference alone. Although this mechanism may initially appear less intuitive, it captures the fact that individuals often engage in behaviours that do not correspond to their preferences. A prominent example is the occupational context, in which individuals may generally prefer their profession but nonetheless encounter tasks or situations that are experienced as aversive yet are performed due to external obligations. Under this mechanism, the real self-concept is expected to remain stable as long as commitment remains stable.

Combination of Approaches

As both mechanisms described above appear psychologically plausible, it seems advisable to initially implement a combination of the two approaches. This allows simulations to explore scenarios in which either preference-based evaluation or situational commitment dominates behavioural decisions, as well as intermediate cases reflecting their interaction.

Experiences Evaluation

So far it has been described how agent specific parameters such as cognitive bias self concept and preferences can be inferred from accumulated experiences. By continuously adding new experiences this process captures the concept of habituation in which parameters are gradually adjusted to reflect new experiences. It is conceivable that human cognition operates in a similar manner aggregating experiences into a construct referred to here as the self concept. In this sense experiences may continue to influence the self even when the individual can no longer recall the specific events that gave rise to them.

At the same time it appears essential that specific experiences can be forgotten or at least re evaluated through targeted interventions. To account for this an accessibility factor is introduced as mentioned earlier. This factor is incorporated as an additional weighting term in the computation of all agent parameters. A gradual reduction of accessibility over time allows the simulation of forgetting curves whereas an increase in accessibility enables the modelling of renewed cognitive engagement with past experiences such as rumination or deliberate reappraisal.

Simulation Processes

Situation Selection

Intervention Mechanisms

Agent Parameters

Updating

Contents

| Title | Author | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Affektive Evaluation | 21.01.2026 | |

| Aggregating Fasets and Traits | 21.01.2026 | |

| Behaviour Bias | 21.01.2026 | |

| Cognitive Bias | 21.01.2026 | |

| Experiences | 21.01.2026 | |

| Features | 21.01.2026 |